Home > Junko's Blog > The 'Era of Turbulence' and Japan's Paths to the Future

April 02, 2013

The 'Era of Turbulence' and Japan's Paths to the Future

from Japan for Sustainability (JFS) Newsletter No.127

http://www.japanfs.org/en/mailmagazine/newsletter/pages/032703.html

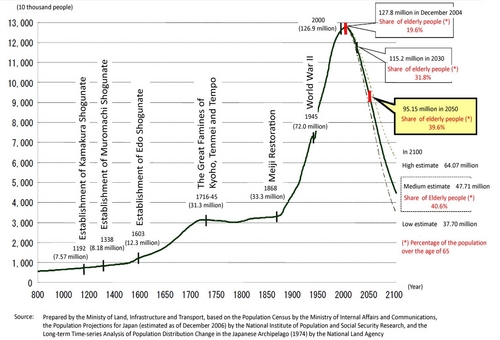

Ahead of other countries in the world, Japan's population has begun to decline. It peaked at 127.84 million people in 2004, when the share of elderly people (aged 65 or over) in the total population was 19.6%. If this trend continues, the population is expected to drop to 115.22 million, with the elderly share of population at 31.8% in 2030, and 95.15 million with a 39.5% (share) in 2050. Japan is facing a rapid population decline and aging of society.

Now that human activity exceeds the Earth's carrying capacity, we might say that countries experiencing population decrease have major opportunities to re-design society so that people can live in genuine happiness, by reviewing the scale of their economy and reducing environmental impacts.

On the other hand, people who believe that the economy should continue growing just as before will reject the reality of population decrease under the excuse of having no attractive alternatives to economic growth. Such people will insist that economic growth is absolutely needed, no matter if the population is declining and the world's consumption is beyond the limits of the Earth.

Since Japan's economic bubble burst at the beginning of the 1990s, growth in the Japanese economy has remained stagnant, and the last two decades have been called "the lost 20 years" for the economy. Although this may be a "problem" from any viewpoint that values economic growth as the ultimate priority, this could be Japan's (unintentional) turning point towards a steady-state economy.

When we reconsider the real meaning of a "sustainable society," the world would gain useful lessons from the experiences, explorations, and trials and errors of Japan in the midst of population decline. JFS will introduce emerging ideas and discussions within this context in future newsletters.

In this issue, we feature an excerpt from "Ikoki-teki Konran (The Era of Turbulence, published by Chikuma Shobo in 2010)," by Katsumi Hirakawa, as the first article in a series to raise the issues from JFS's point of view.

------------------------

The Significance of this "Once-a-Century Crisis"

What kind of era are we living in now? An era strongly influences people's way of thinking and perceptions in a certain direction. We do not exactly think and feel as freely as we think. Now that several years have passed since 2008, when the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers triggered a worldwide financial crisis, we might be in the midst of a turbulent time, facing a major turning point in shifting from the dominant paradigm of the era.

The worldwide financial crisis after 2008 is referred to as a "once-a-century crisis," which is comparable to the Great Depression in 1929. This implies that the latest financial crisis is one of the events in the cycle of economic ups and downs historically repeated since the tulip mania in the seventeenth century.

However, the financial crisis this time seems like an event in the era of turbulence, emerging at a qualitative turning point in our history. This is because the 2008 crisis could be interpreted to contain two aspects: one is a political and economic system change from the upper to lower tiers of society, and the other is structural change from the lower to upper tiers in society and people's lives. In the midst of this crisis, the perception of people in their daily lives has been shaken, and Japan is the most destabilized in the world because it had raced so quickly to embrace the capitalist production model.

It is not exactly the latest financial crisis that triggered disorder in the Japanese economy, which then contributed to the perceptional change among Japanese people. The causality is the reverse. People's perception in life changed first, and this became the turning point of the era, causing turbulence.

But most economists and politicians in Japan don't see things like that. They see the financial crisis as merely a failure in the operation of the financial system, and believe that the economy will grow again. They also expect that technological innovation will solve our challenges in environmental destruction and widening economic and social disparities, and get the economy back on track to grow again.

If it was a "once-a-century crisis," the terms for thinking about the problem also have to be ones that last for a period of 100 years; however in reality, we hear decades-long familiar terms premised on a soaring economy, such as shareholders' profits and economic-growth strategies. Use of these terms is exactly one result of the once-in-a-century problem, which could be a factor in causing confusion.

Again, we should not think that the social turmoil was caused by the financial crisis. The financial crisis was only one indication of confusion in the transitional period. Some of our current problems, including environmental destruction, widening income gaps among people, population decrease, prolonged deflation, the popular language of the time, and changing values, are also aspects of confusion in the transitional period. They are not the cause of the confusion but the result.

Is Japan's Population Decrease a Serious Problem?

According to the hypothesis by French demographer Emmanuel Todd, the improvement of women's literacy rates and social status in democratization would cause a shift from population growth toward decline in most countries and regions over time. Japan's population is already swinging back from an increasing trend.

Politicians as well as business leaders keep saying that a population decrease is a serious problem. They say that social vitality will be lost if the population decreases, but it is doubtful whether their claim has any reasonable grounds. Japan has never experienced such a population decrease in its history, so the assertion that a population decrease causes economic stagnation and decline in social vitality is only an assumption.

When a population decreases, the overall gross domestic product (GDP) growth slows down or diminishes. This is because GDP growth is closely related to the total labor population. Japan's GDP per capita actually has remained stagnant since around 2000. On the other hand, Luxembourg in Western Europe has the world's largest GDP growth per capita with a population of less than 500,000 people. A smaller population doesn't necessarily result in GDP decline per capita. Other factors can be related to a diminishing GDP, such as widening income gaps among people and demographic structural changes.

Without a doubt, Japan's total population will decrease. Japan has not experienced a continuous shrinking of economic scale associated with population decrease in its long history; therefore, the past incidents are almost useless as effective measures against the problem of population and economic declines. To illustrate strategies, it is necessary to reestablish ideas on work and values suitable for a mature society with a smaller population.

Economic growth has created consumerism, the advance of democracy, improvement of women's status, and lower birth rates. It may have been inevitable that due to population decrease Japan would eventually shift to a social structure incapable of making continuous economic growth.

Japanese business leaders often criticize the lack of an economic growth roadmap in the national strategy; however, the stagnation of GDP growth is not caused by the lack of a strategy but by economic growth itself. Moreover, as the result of consumerism, the advance of democracy, expansion of urban cities, transformation or collapse of family structure, which were all caused by economic growth, Japan is facing the problem of population decrease for the first time in its history.

The effective measure to stop the population decrease is not a further economic expansion that business leaders often advocate. Similarly, the effective measure to continue economic growth is not a return to population growth. Rather, the opposite idea of making a sustainable society without economic growth is more important. The problem is not the lack of a growth strategy. The real problem is the lack of a strategy for running society without growth.

The Era of Turbulence

For the time being, confusion -- such as trial-and-error efforts by those who desire economic growth, ruined work ethics caused by excessive money worship and expanding disparities -- will continue in this transitional period. This is an indispensable confusion which helps us to re-examine our present society, and we can expect another paradigm, which is different from the present paradigm based on the competition principle, to be created.

One of the confusions caused by actions from the growth-oriented perspective is the collapse of business morals in order to profit. We have seen examples, such as food-labeling fraud and forgery of construction data not meeting architectural safety standards. This moral collapse comes from our faith that a constantly-growing economy means the increase of wealth or money, and that it is an absolute good. Nobody would argue against cost-cutting efforts. For example, the unethical behavior of using expired food materials is also a result of actions to reduce costs. This is not because business people lack an ethical sense, but because they went too far in following business ethics guided by market principles, in other words, the pursuit of profit above all.

Widening social disparity is another state of confusion in the transitional period. Competition is a game based on the presumption that the strongest should win. The majority of Japanese people accepted competition rules because they thought these rules are an appropriate system for economic growth. In Japan's modernization process, it was inevitable to adopt competition rules to maximize efficiency. However, at the same time, the introduction of the rules led to an expanding gap between competitors, and another gap began to be perceived.

Moreover, bankruptcies are on the rise. In the 1970s and 1980s, the strength of Japanese companies was maintained by strong solidarity in networks of manufacturers, as well as accumulated technologies in small and tiny companies, and manufacturers who were proud of their own craftsmanship. Most of the employees of tiny companies worked not only for a salary, but also for their sense of ethics as professionals.

Such an irrational work ethos, however, was lost along with the emergence of temporary staff services, overseas transfer of production plants, and technological innovation toward mechanization. Employees became aware of individualism and began to calculate the balance between excess labor and benefit, while employers began to consider adjustments in their workforces to maximize short-term profit. Under such circumstances, only the "irrationality" of lifetime employment and the seniority system gained attention, and very small manufacturers, which had been supporting such a system, lost their basis for survival.

How to Think about the Future

We should understand that the various problems expected in the future Japan are issues in a different context from our challenges in the past, when the economy continued to grow. That is, we cannot learn much from past experiences to find answers to solve today's difficulties during the transition time. Learning from the past could be useful in the same historical context. But conversely, dependence on past methods may reinforce confusion in the present.

Though it is almost impossible for me to advise others on what to think about these unknown problems, it is possible to identify the sources from which context any simple measures might come to help us deal with the issues. What we know is that, in the transitional period, it is meaningless to seek clues from past experience on how we should deal with problems. We don't know what stance we should take unless we consider why we think of unknown problems this way, and we should keep asking fundamental questions about what kind of thinking we should avoid when we see things.

In my book "Keizai Seicho to iu Yamai (A malady Called Economic Growth)" published by Kodansha in 2009, I used the word "malady" to describe the inability to take into account other possibilities due to clinging to the existing growth-oriented paradigm, despite the possibility of being in the middle of a great paradigm shift. I cannot explain what the new paradigm is like in a single word; however, what I can say is that we should not think in the same way as in the economic growth phase, and not act according to growth-oriented assumptions and preconceptions.

------------------------

Closing comment: Hirakawa's point of view gives us useful hints on how we should deal with various problems and disruptions of modern society and what we should aim for as we move ahead. Stay tuned for more coverage of these topics in our future issues of the JFS newsletter.

Written by Junko Edahiro and Naoko Niitsu